Works of Love

A Newsletter of The Institute for Research on Unlimited Love

June 1, 2016

Greetings Friends:

This newsletter touches on hope for deeply forgetful people, drawing on my memories of Aaron Copland's visit to St. Paul's School and a reflection on his passing away from Alzheimer's disease in 1990. In two weeks I will be doing the keynote address for the annual International Dementia Conference in Sydney. I have entitled it "Hope, Continuity of Self-Identity, and Deeply Forgetful People." Hope for caregivers lies in being open to surprises, and Aaron Copland surprised everyone one day when everyone in the room thought he was "gone," "a shell," "a husk." But he was much more there than "gone," even though he could not communicate by speech. He surprised the heck out of people by rising up to play the six key notes of Appalachian Spring on the piano.

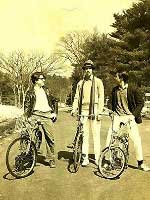

That’s me on the left up at school with buddies Paul and Hap. |

In 1967 my then 18-year-old older brother Henry Post, who was quite a good bassoonist, invited the composer Aaron Copland up to St. Paul's in Concord, New Hampshire. To Henry's surprise, Copland agreed, and he spent two weeks in Scudder House on the SPS campus. About two dozen students in the school band, along with band director Paul Trafton Giles, were able to speak with him about music and composition. I can recall Rev. Matt Warren, the then Headmaster, introducing Copland in the Chapel. The applause were modest because Copland was known mainly to the small set of musicians and not so much to the hockey players. Someone whispered to me that morning, "Who the heck is that guy?" I did meet Copland, shake his hand, and listen to him give a talk. I even played a little rag time (Scott Joplin) guitar for him and a line or two of Villa Lobos, and he offered some very nice comments. I told him how even I could appreciate Appalachian Spring (I was nowhere at all near the musician my brother was), because "it just captures the ice and snow melting so perfectly!" "Well Stephen," responded Copland, "truth is I wrote that for Martha Graham and it had no title, so they decided to call it what they did. But I personally have not driven much west of the Hudson, though I have flown to Pittsburgh and the like." "Well whatever, but it sounds that way to me Sir, it's great!" He smiled and I laughed.

Aaron Copland |

Copland, a Brooklyn native, was living in Peekskill, New York, in 1990, when he passed away with Alzheimer's. In 1987, some very distinguished musicians went up there to visit him but he could not communicate verbally at all. They were very sad indeed. However, Copland was still there underneath the breakdown in speech. He rose up and went to the piano, and there he played the six notes that comprise the two chords around which Appalachian Spring is constructed. Below, please view the YouTube video of Leonard Slatkin, conductor of the Detroit Symphony, as he describes Copland that day. Slatkin comments, "It was as if he was trying to say that despite all, I am still here." Slatkin's two-minute reflection is followed by a great performance.

YouTube: Slatkin conducts Appalachian Spring